@BNV Hi, das hier ist die beste Beschreibung die ich je zu dieser Zahl gelesen habe.

:) Les sie dir mal durch. Ich hoffe du kannst englisch.

;) http://waitbutwhy.com/2014/11/1000000-grahams-number.htmlGraham’s NumberYou know how sometimes you go through life, and you’re lost but you don’t even know it, and then one day, the right person comes along and you realize what you had been looking for this whole time?

That’s how I feel about Graham’s number.

Huge numbers have always both tantalized me and given me nightmares, and until I learned about Graham’s number, I thought the biggest numbers a human could ever conceive of were things like “A googolplex to the googolplexth power,” which would blow my mind when I thought about it. But when I learned about Graham’s number, I realized that not only had I not scratched the surface of a truly huge number, I had been incapable of doing so—I didn’t have the tools. And now that I’ve gained those tools (and you will too today), a googolplex to the googolplexth power sounds like a kid saying “100 plus 100!” when asked to say the biggest number he could think of.

Before we dive in, why is Graham’s number even a number people talk about?

I’m not gonna really explain this because the explanation is really boring and confusing—here’s the official problem Ronald Graham (a living American mathematician) was working on when he came up with it:

Connect each pair of geometric vertices of an n-dimensional hypercube to obtain a complete graph on 2n vertices. Color each of the edges of this graph either red or blue. What is the smallest value of n for which every such coloring contains at least one single-colored complete subgraph on four coplanar vertices?

I told you it was boring and confusing. Anyway, there’s no single answer to the problem, but Graham’s proof includes a lower and upper bound, and Graham’s number was one version of an upper bound for n that Graham came up with.

He came up with the number in 1977, and it gained recognition when a colleague wrote about it in Scientific American and called it “a bound so vast that it holds the record for the largest number ever used in a serious mathematical proof.” The number ended up in the Guinness Book of World Records in 1980 for the same reason, and though it has today been surpassed, it’s still renowned for being the biggest number most people ever hear about. That’s why Graham’s number is a thing—it’s not just an arbitrarily huge number, it’s actually relevant in the world of math.

So anyway, I said above that I had been limited in the kind of number I could even imagine because I lacked the tools—so what are the tools we need to do this?

It’s actually one key tool: the hyperoperation sequence.

The hyperoperation sequence is a series of mathematical operations (e.g. addition, multiplication, etc.), where each operation in the sequence is an iteration up from the previous operation. You’ll understand in a second. Let’s start with the first and simplest operation: counting.

Operation Level 0 – Counting

If I have 3 and I want to go up from there, I go 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and so on until I get where I want to be. Not a high-powered operation.

Operation Level 1 – Addition

Addition is an iteration up from counting, which we can call “iterated counting”—so instead of doing 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, I can just say 3 + 4 and skip straight to 7. Addition being “iterated counting” means that addition is like a counting shortcut—a way to bundle all the counting steps into one, more concise step.

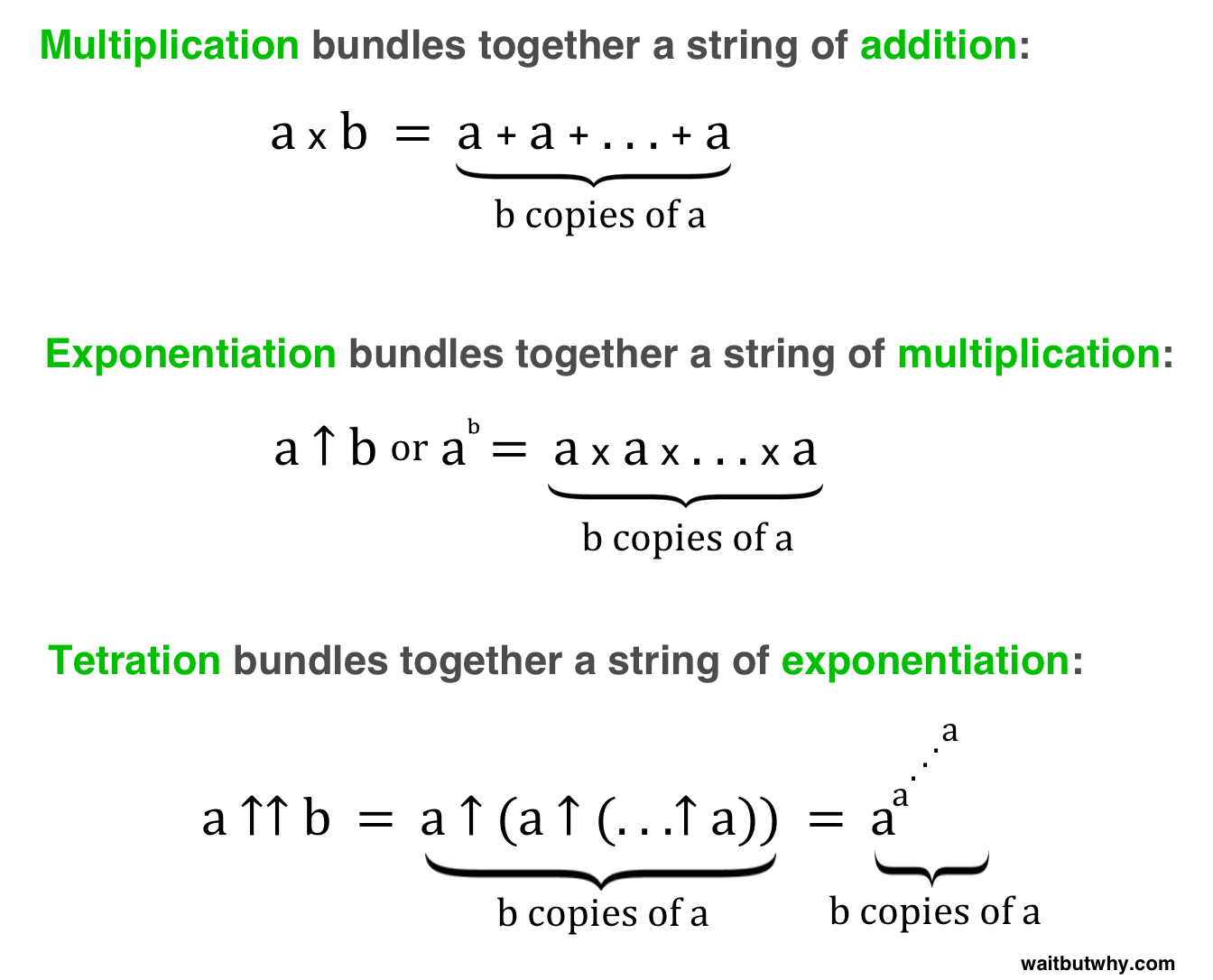

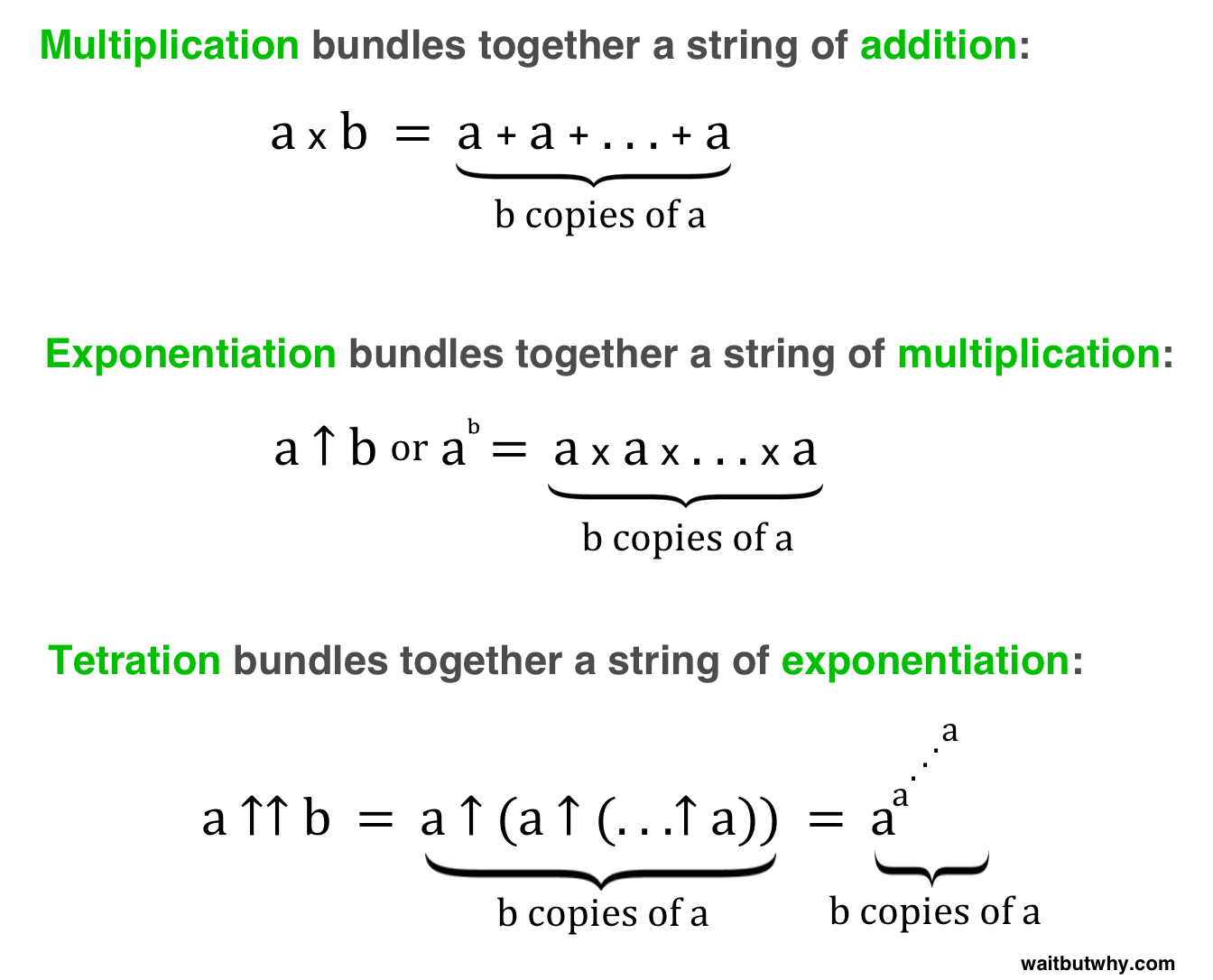

Operation Level 2 – Multiplication

One level up, multiplication is iterated addition—an addition shortcut. Instead of saying 3 + 3 + 3 + 3, multiplication allows us to bundle all of those addition steps into one higher-operation step and say 3 x 4. Multiplication is a more powerful operation than addition and you can create way bigger numbers with it. If I add two eight-digit numbers together, I’ll end up with either an eight or nine-digit number. But if I multiply two eight-digit numbers together, I end up with either a 15 or 16-digit number—much bigger.

Operation Level 3 – Exponentiation (↑)

Moving up another level, exponentiation is iterated multiplication. Instead of saying 3 x 3 x 3 x 3, exponentiation allows me to bundle that string into the more concise 3^4.

Now, the thing is, this is where most people stop. In the real world, exponentiation is the highest operation we tend to ever use in the hyperoperation sequence. And when I was envisioning my huge googolplexgoogolplex number, I was doing the very best I could using the highest level I knew—exponentiation. On Level 3, the way to go as huge as possible is to make the base number massive and the exponent number massive. Once I had done that, I had maxed out.

The key to breaking through the ceiling to the really big numbers is understanding that you can go up more levels of operations—you can keep iterating up infinitely. That’s the way numbers get truly huge.

And to do this, we need a different kind of notation. So far, we’ve worked with a different symbol on each level (+, x, and a superscript)—but we don’t want to have to remember a ton of different symbols if we’re gonna be working with a bunch of different operations levels. So we’ll use Knuth’s up-arrow notation, which is one symbol that can be used on any level.

Knuth’s up-arrow notation starts on Operation Level 3, replacing exponentiation with a single up arrow: ↑. So to use up-arrow notation, instead of saying 3^4, we say 3 ↑ 4, but they mean the same thing.

3 ↑ 4 = 81

2 ↑ 3 = 8

5 ↑ 5 = 3,125

1 ↑ 38 = 1

Got it? Good.

Now let’s move up a level and start seeing the insane power of the hyperoperation sequence:

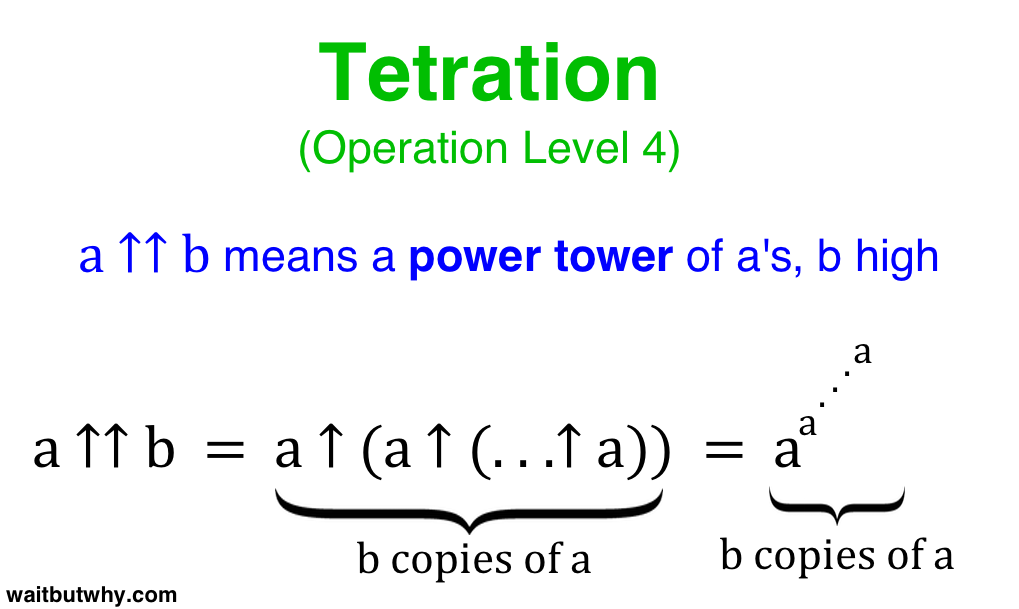

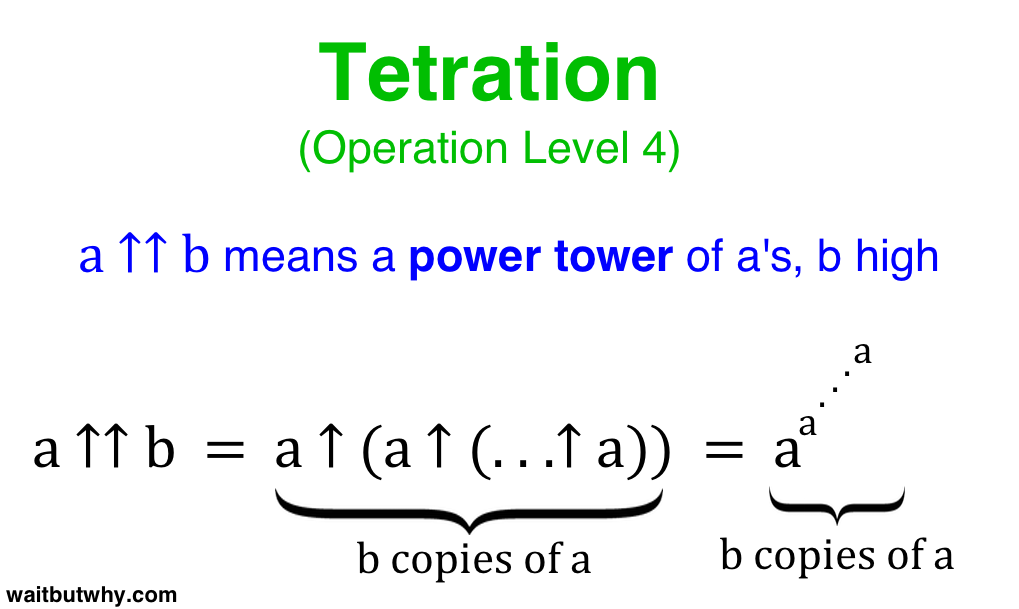

Operation Level 4 – Tetration (↑↑)

Tetration is iterated exponentiation. Before we can understand how to bundle a string of exponentiation the way exponentiation bundles a string of multiplication, we need to understand what a “string of exponentiation” even is.

So far, all we’ve done with exponentiation is one computation—a base number and a power it’s raised to. But what if we put two of these computations together, like:

2^2^2

We get a power tower. Power towers are incredibly powerful, because they start at the top and work their way down. So 2^2^2 = 2(2^2) = 2^4 = 16. Nothing that impressive yet, but check out:

3^3^3^3

Using parentheses to emphasize the top down order: 3^3^3^3 = 3^3^(3^3) = 3^3^27 =3(3^27) = 37,625,597,484,987 = a 3.6 trillion-digit number

Remember, a googol and its universe-filling microscopic mini-sand is only a 100-digit number. So all it takes is a power tower of 3s stacked 4 high to dwarf a googol, as well as 10^185, the number of Planck volumes to fill the universe and our physical world maximum. It’s not as big as a googolplex, but we can take care of that easily by just adding one more 3 to the stack:

3^3^3^3^3 = 3(3^3^3^3) = 3(3.6 trillion-digit number) = way bigger than a googolplex, which is 10^(100-digit number). As for a googolplex itself, power towers allow us to immediately humiliate it by writing it as:

10^10^100 or, more typically, 10^10^102. So you can imagine what kind of number you get when you start making tall power towers. Tetration is intense.

Now those towers are Level 3, exponential strings, the same way 3 x 3 x 3 x 3 is a Level 2, multiplication string. We use Level 3 to bundle that Level 2 string into 3^4, or 3 ↑ 4. So how do we use Level 4 to bundle an exponential string? Double arrows.

3^3^3^3 is the same as saying 3 ↑ (3 ↑ (3 ↑ 3)). We bundle those 4 one-arrow 3s into 3 ↑↑ 4.

Likewise, 3 ↑↑ 5 = 3 ↑ (3 ↑ (3 ↑ (3 ↑ 3))) = 3^3^3^3^3

4 ↑↑ 7 = 4 ↑ (4 ↑ (4 ↑ (4 ↑ (4 ↑ (4 ↑ 4))))) = a power tower of 4s 7 high.

Here’s the general rule:

tetration generally

We’re about to move up another level, and this is about to become more complex, so before we move on, make sure you really understand Level 4 and what ↑↑ means—just remember that a ↑↑ b is a power tower of a’s, b high.

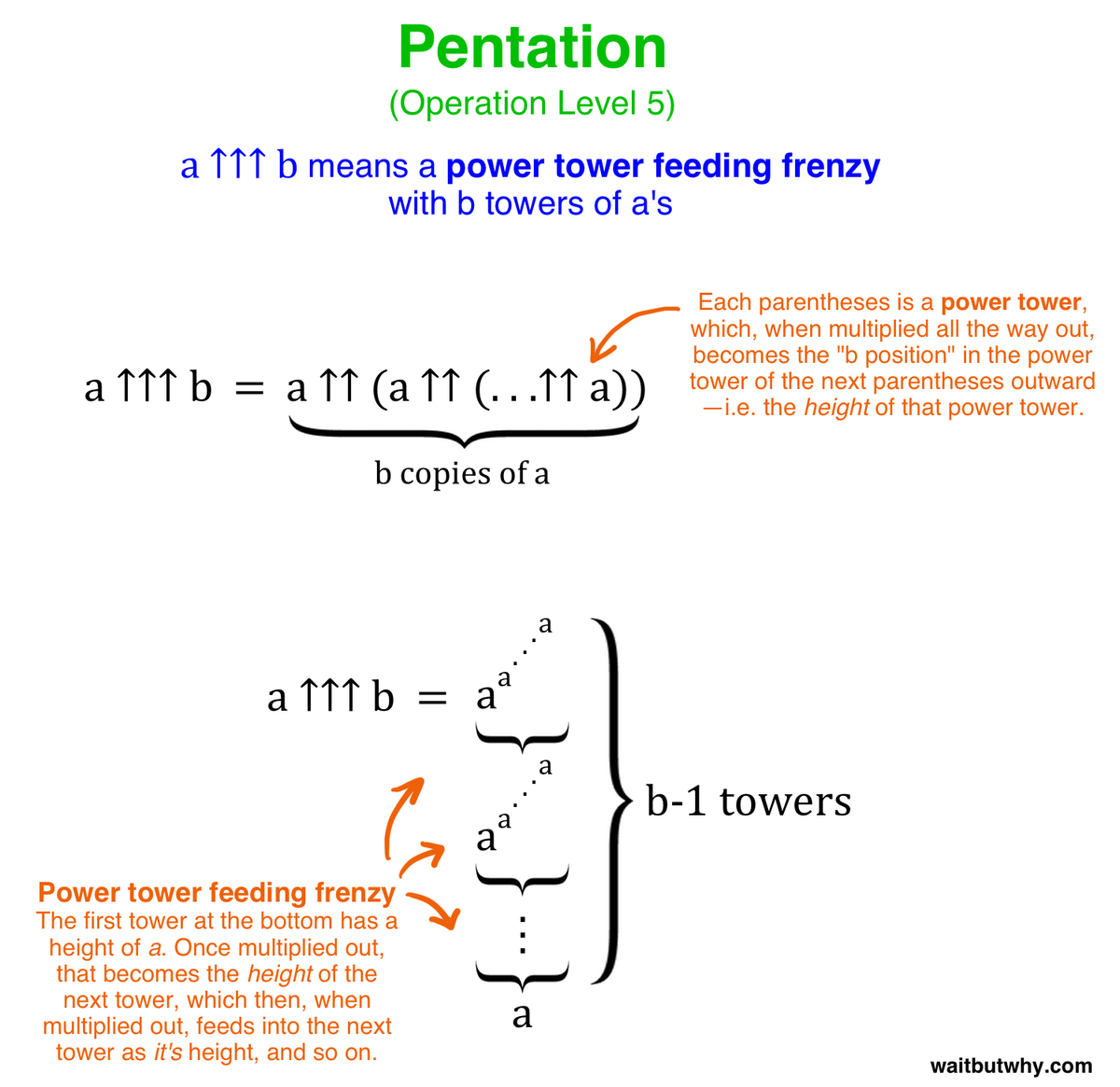

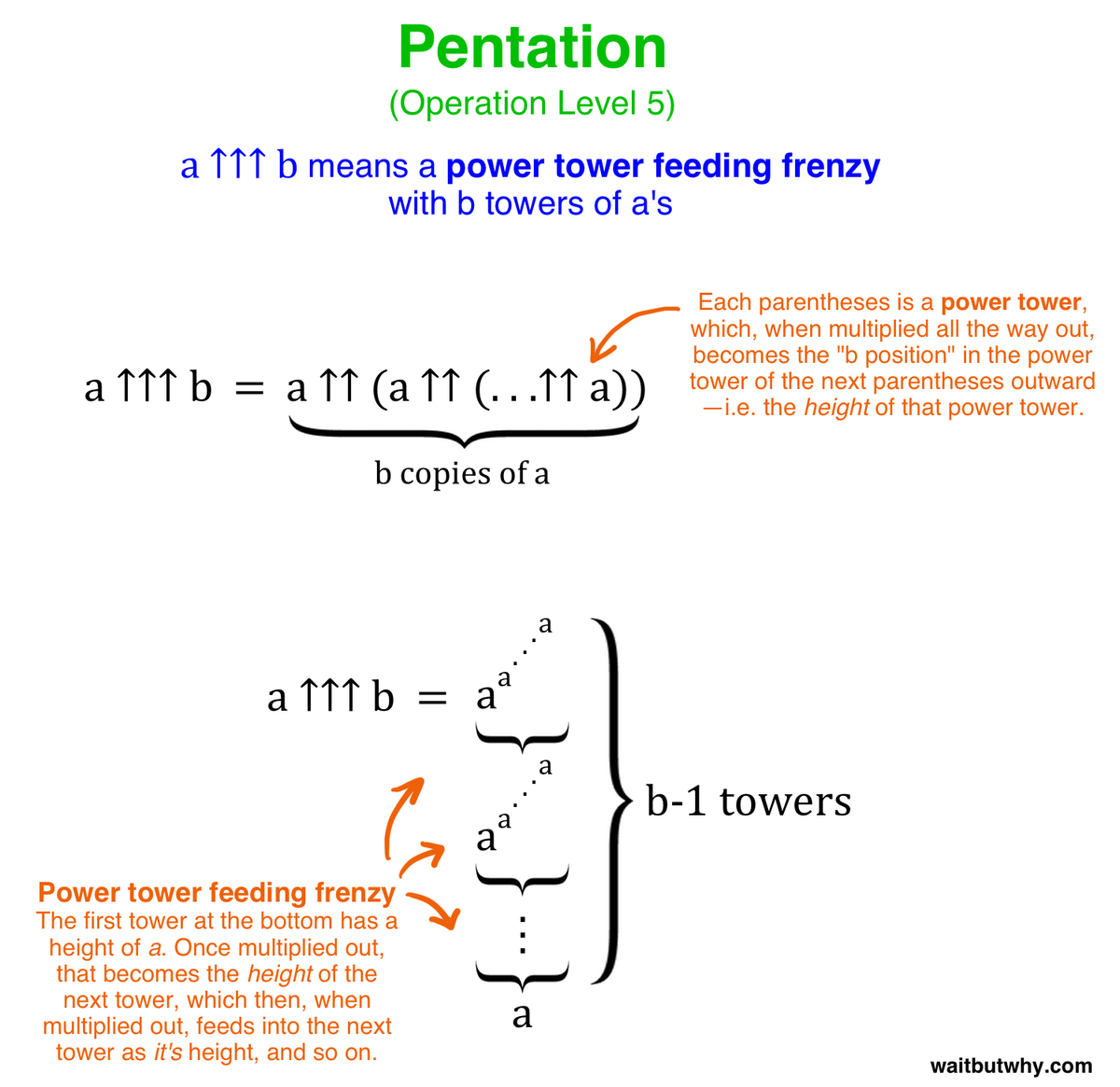

Operation Level 5 – Pentation (↑↑↑)

Pentation, or iterated tetration, bundles double arrow strings together into a single operation.

The pattern we’ve seen is each new level bundles a string of the previous level together by using a b term as the length of the string. For example:

string bundle examples

In each case, a is the base number and b is the length of the string being bundled.

So what does pentation bundle together? How can you have a string of power towers?

The answer is what I call a “power tower feeding frenzy”. Here’s how it works:

You have a string of power towers standing next to each other, in a particular order, all using the same base number. The thing that differs between them is the height of each tower. The first tower’s height is the same number as the base number. You process that tower down to its full expanded outcome, and that outcome becomes the height of the next tower. You then process that tower, and the outcome becomes the height of the next tower. And so on. Each tower’s outcome “feeds” into the next tower and becomes its height—hence the feeding frenzy. Here’s why this happens:

3 ↑↑↑ 4 means a string of (3 ↑↑ 3) operations, 4 long. So:

3 ↑↑↑ 4 = 3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3))

Remember, when you see ↑↑ it means a single power tower that’s b high, so:

3 ↑↑↑ 4 = 3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3)) = 3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3^3^3)

Now, you might remember from before that 3^3^3 = 3^27 = 7,625,597,484,987. So:

3 ↑↑↑ 4 = 3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3)) = 3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3^3^3) = 3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 7,625,597,484,987)

So the first tower of height 3 processed down into 7 trillion-ish. Now the next parentheses we’re dealing with is (3 ↑↑ 7,625,597,484,987), where the outcome of the first tower is the height of this second tower. And how high would that tower of 7 trillion-ish 3s be?

Well if each 3 is two centimeters high, which is about how big my written 3’s are, the tower would rise about 150 million kilometers high, which would touch the sun. Even if we used tiny, typed 2mm 3’s, our tower would reach the moon and back to the Earth and back to the moon forty times before finishing. If we wrote those tiny 3’s on the ground instead, the tower would wrap around the earth 400 times. Let’s call this tower the “sun tower,” because it stretches all the way to the sun. So what we have is:

3 ↑↑↑ 4 = 3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3)) = 3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3^3^3) = 3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 7,625,597,484,987) = 3 ↑↑ (sun tower)

This final 3 ↑↑ (sun tower) operation is a power tower of 3’s whose height is the number you get when you multiply out the entire sun tower (and this final tower we’re building won’t even come close to fitting in the observable universe). And we don’t get to our final value of 3 ↑↑↑ 4 until we multiply out this final tower.

So using ↑↑↑, or pentation, creates a power tower feeding frenzy, where as you go, each tower’s height begins to become incomprehensible, let alone the actual final value. Written generally:

Original anzeigen (0,1 MB)

Original anzeigen (0,1 MB)pentation generally

We’re gonna go up one more level—

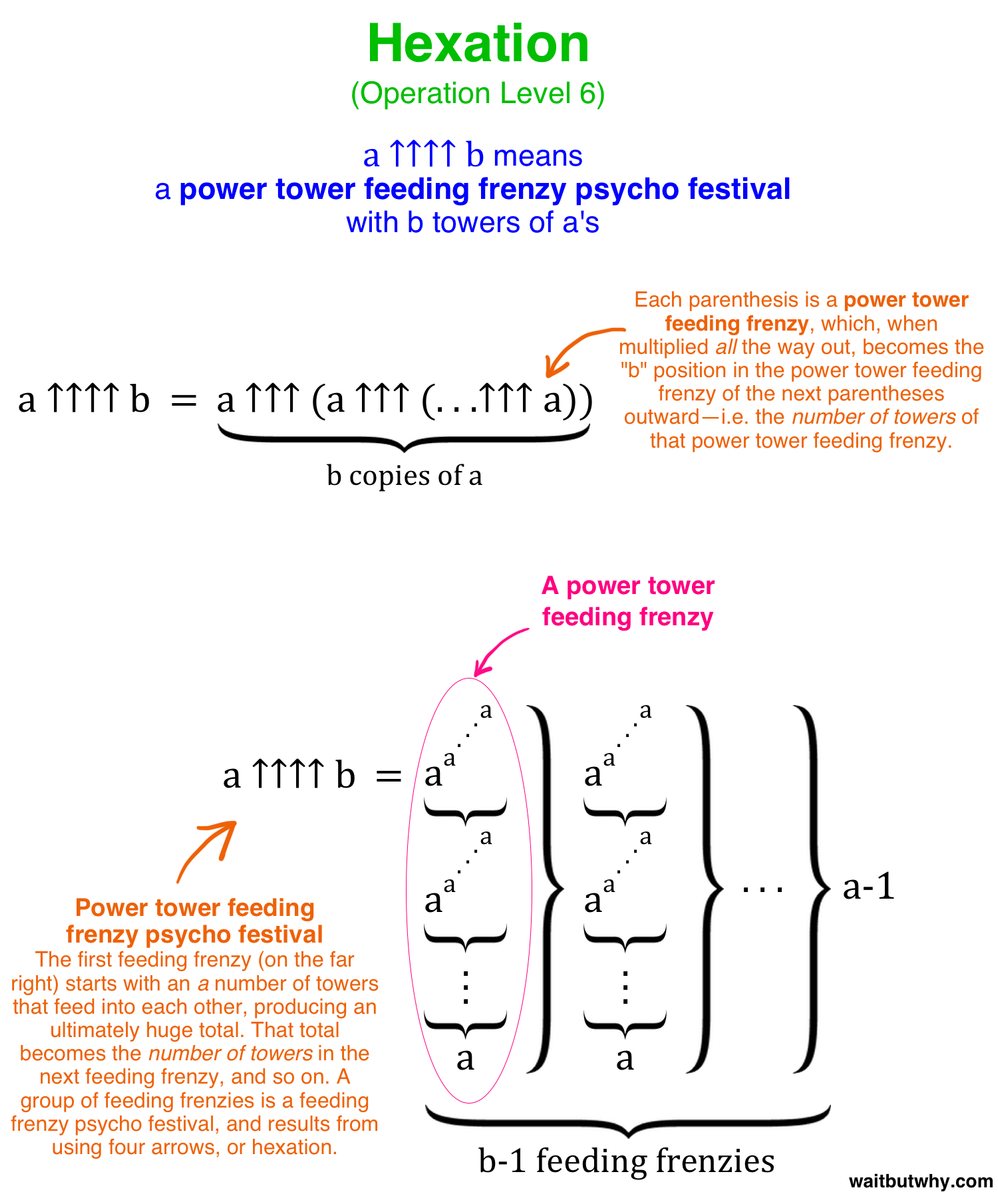

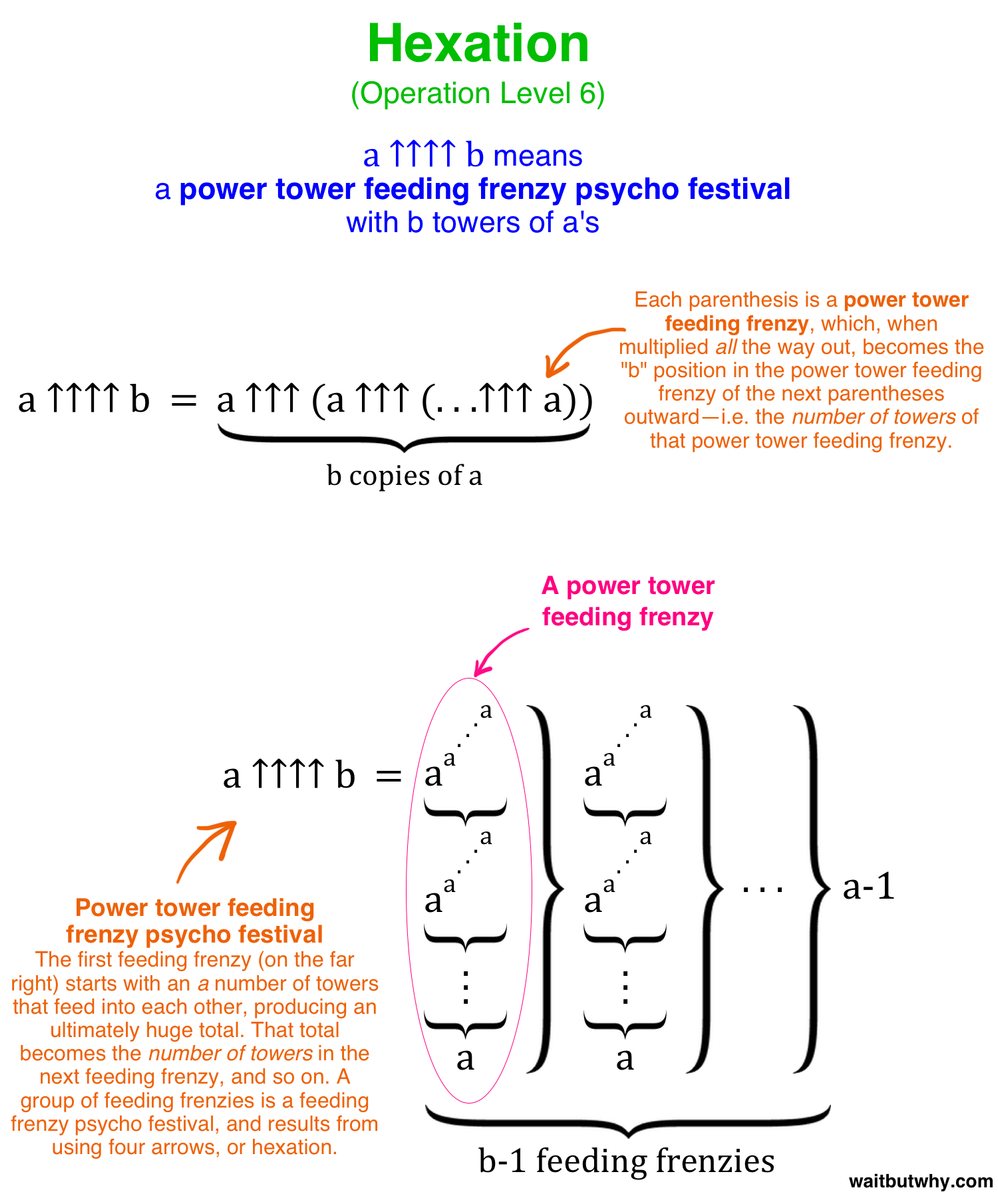

Operation Level 6 – Hexation (↑↑↑↑)

So on Level 4, we’re dealing with a string of Level 3 exponents—a power tower. On Level 5, we’re dealing with a string of Level 4 power towers—a power tower feeding frenzy. On Level 6, aka hexation or iterated pentation, we’re dealing with a string of power tower feeding frenzies—what we’ll call a “power tower feeding frenzy psycho festival.” Here’s the basic idea:

A power tower feeding frenzy happens. The final number the frenzy produces becomes the number of towers in the next feeding frenzy. Then that frenzy happens and produces an even more ridiculous number, which then becomes the number of towers for the next frenzy. And so on.

3 ↑↑↑↑ 4 is a power tower feeding frenzy psycho festival, during which there are 3 total ↑↑↑ feeding frenzies, each one dictating the number of towers in the next one. So:

3 ↑↑↑↑ 4 = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ 3))

Now remember from before that 3 ↑↑↑ 3 is what turns into the sun tower. So:

3 ↑↑↑↑ 4 = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ 3)) = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ (sun tower))

Since ↑↑↑ means a power tower feeding frenzy, what we have here with 3 ↑↑↑ (sun tower) is a feeding frenzy with a multiplied-out-sun-tower number of towers. When that feeding finally finishes, the outcome becomes the number of towers in the final feeding frenzy. The psycho festival ends when that final feeding frenzy produces it’s final number. Here’s hexation explained generally:

Original anzeigen (0,2 MB)

Original anzeigen (0,2 MB)hexation generally

And that’s how the hyperoperation sequence works. You can keep increasing the arrows, and each arrow you add dramatically explodes the scope you’re dealing with. So far, we’ve gone through the first seven operations in the sequence, including the first four arrow levels:

↑ = power

↑↑ = power tower

↑↑↑ = power tower feeding frenzy

↑↑↑↑ = power tower feeding frenzy psycho festival

So now that we have the toolkit, let’s go through Graham’s number:

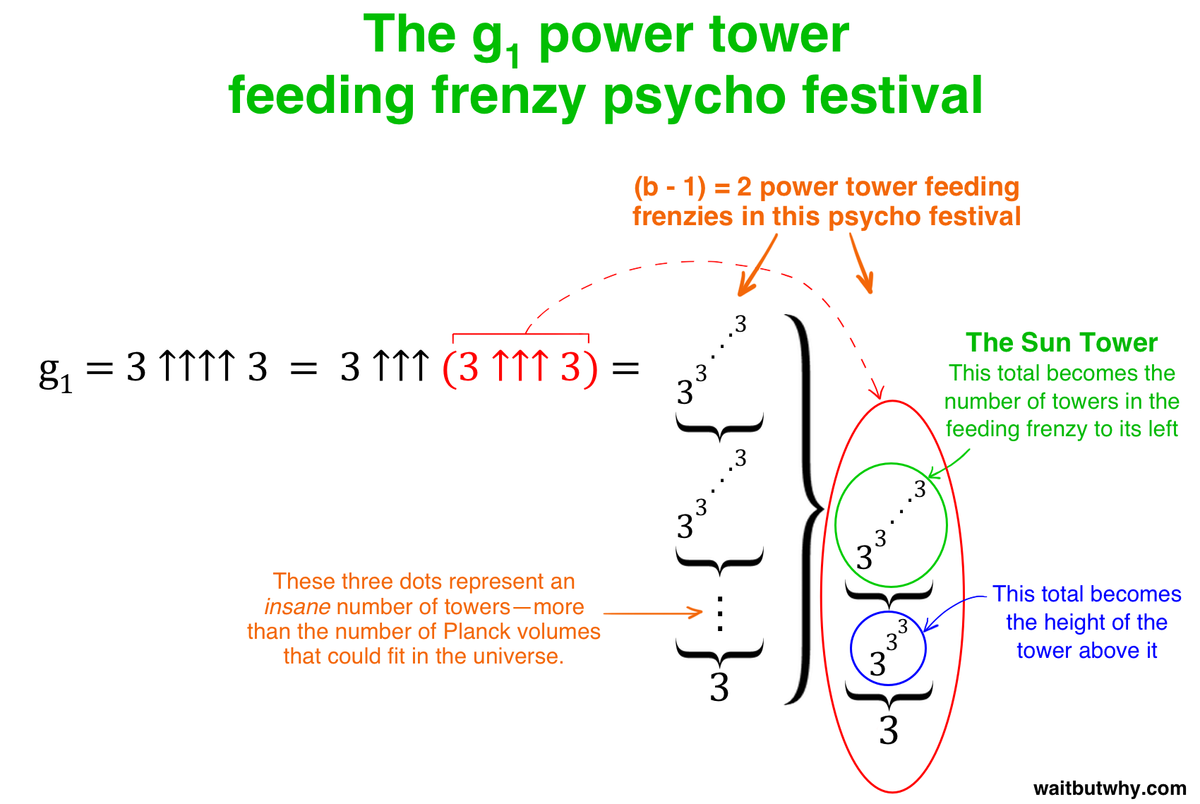

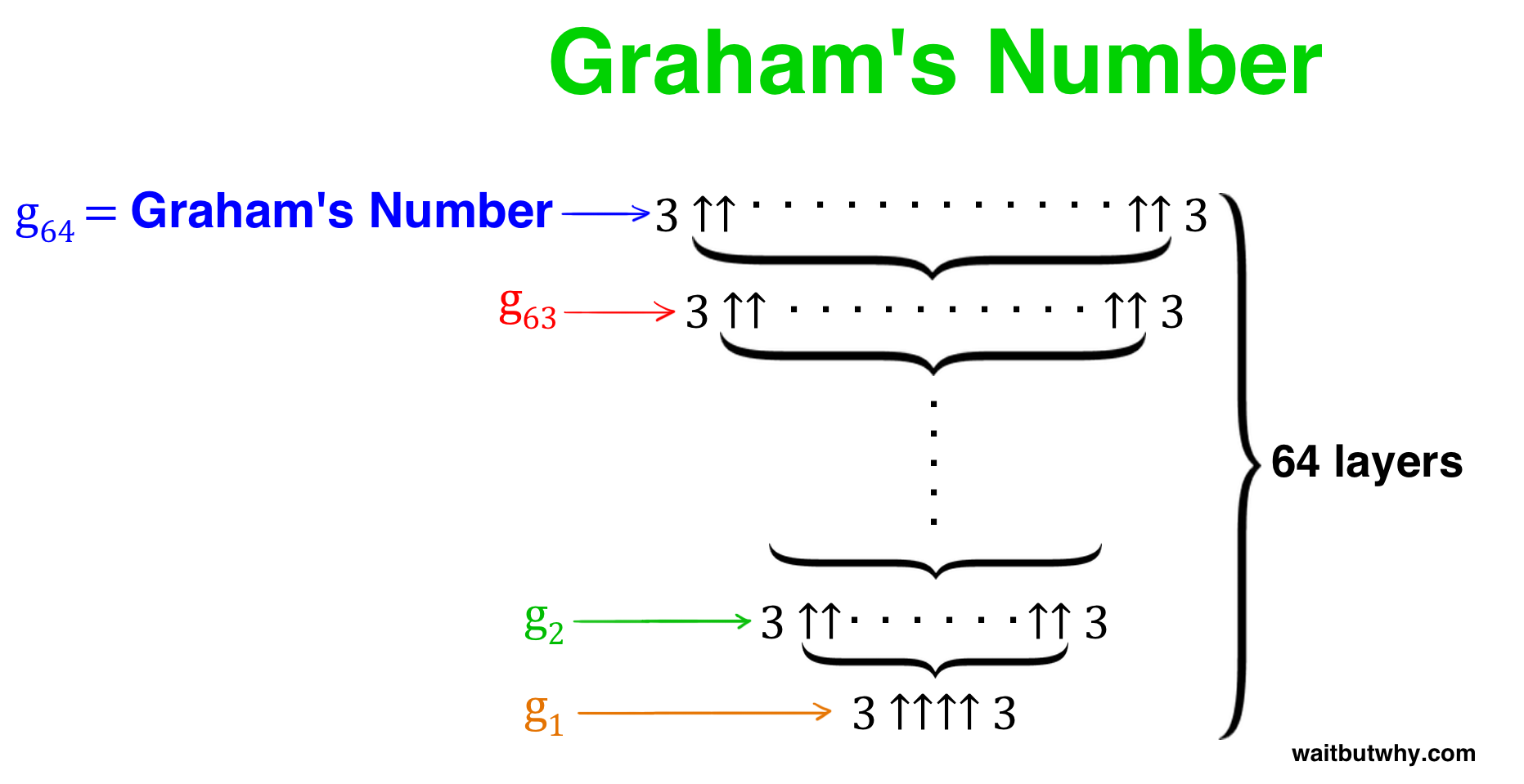

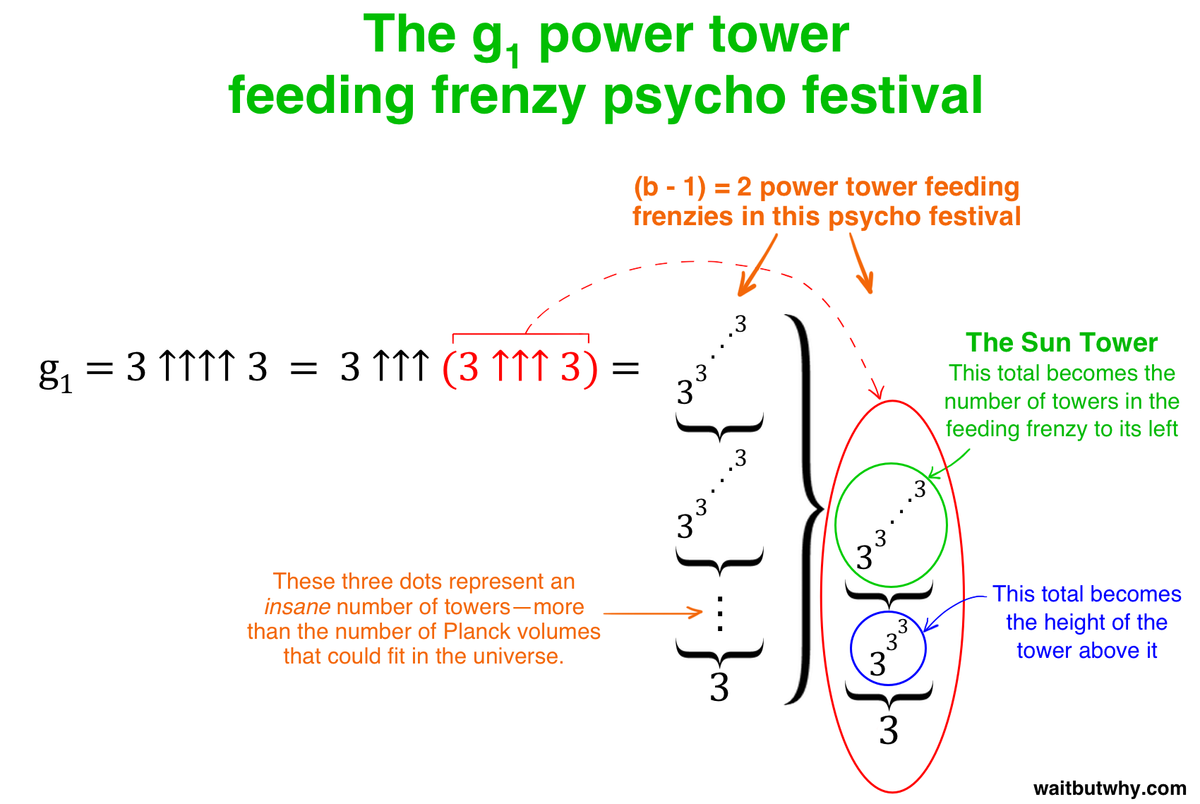

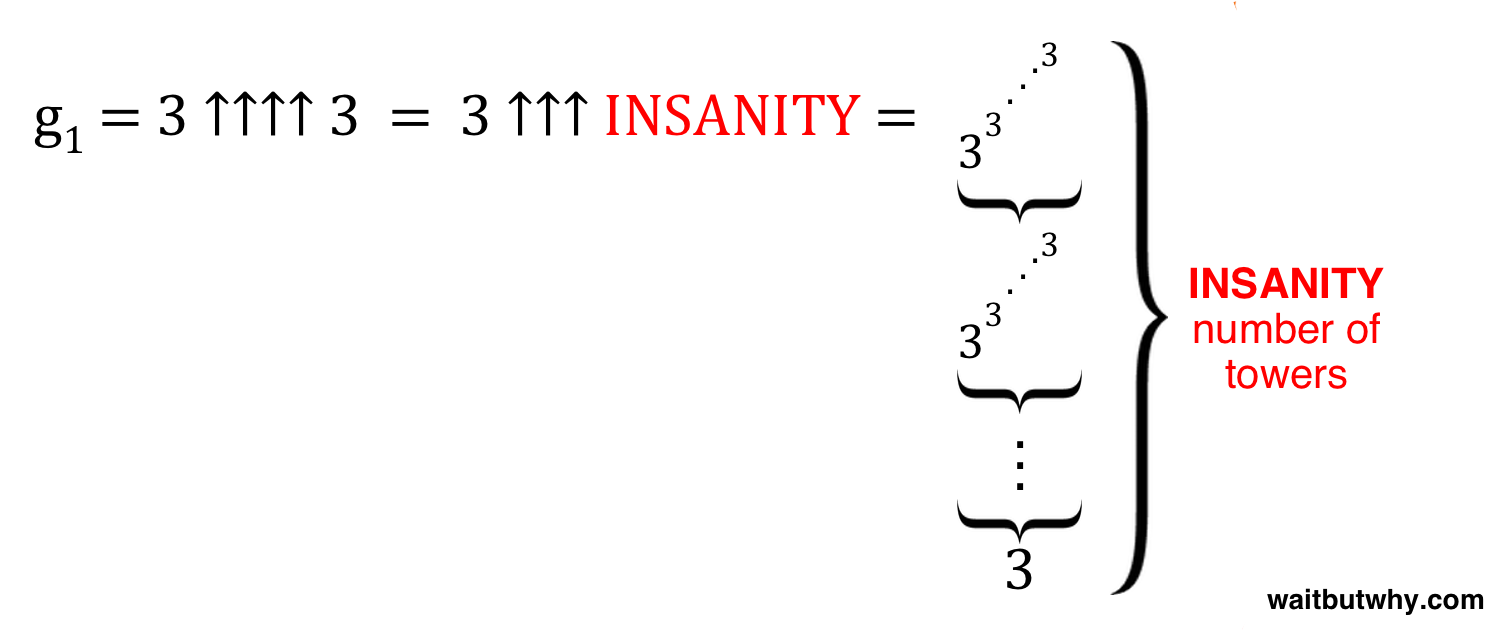

Graham’s number is going to be equal to a term called g64. We’ll get there. First, we need to start back with a number called g1, and then we’ll work our way up. So what’s g1?

g1 = 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3

Hexation. You get it. Kind of. So let’s go through it.

Since there are four arrows, it looks like we have a power tower feeding frenzy psycho festival on our hands. Here’s how it looks visually:

Original anzeigen (0,2 MB)

Original anzeigen (0,2 MB)grahams festival

So g1 = 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3 = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ 3), and we have two feeding frenzies to worry about. Let’s deal with the first one (in red) first:

g1 = 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3 = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ 3) = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3))

So this first feeding frenzy has two ↑↑ power towers. The first tower (in blue) is a straightforward little one because the value of b is only 3:

g1 = 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3 = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ 3) = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3)) = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3^3^3)

And we’ve learned that 333 = 7,625,597,484,987, so:

g1 = 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3 = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ 3) = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3)) = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3^3^3) = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 7,625,597,484,987)

And we know that (3 ↑↑ 7,625,597,484,987) is our 150km-high sun tower:

g1 = 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3 = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ 3) = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3)) = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 3^3^3) = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑ 7,625,597,484,987) = 3 ↑↑↑ (sun tower)

To clean it up:

g1 = 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3 = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ 3) = 3 ↑↑↑ (sun tower)

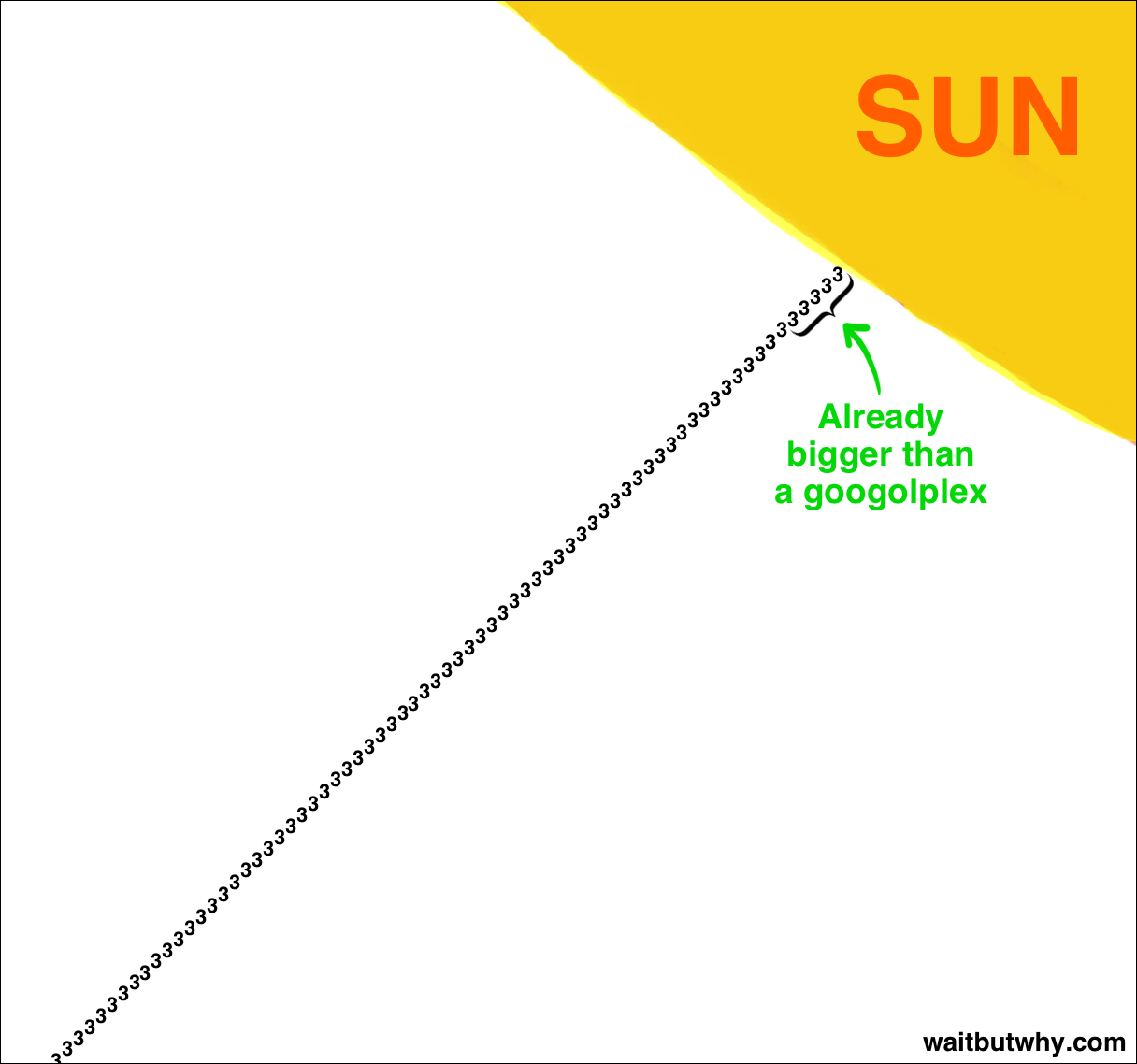

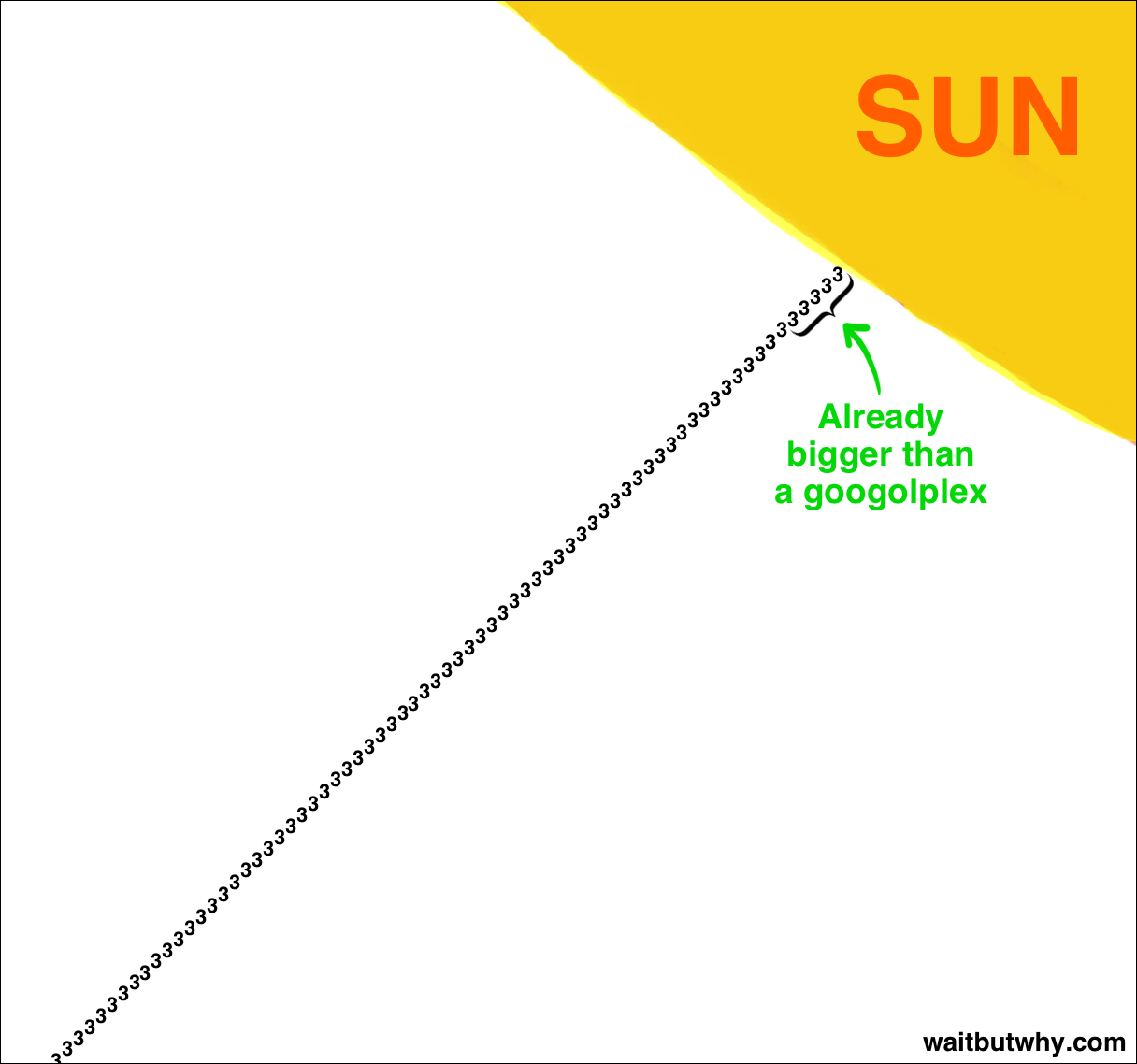

So the first of our two feeding frenzies has left us with an epically tall sun tower of 3’s to multiply down. Remember how earlier we showed how quickly a power tower escalated:

3 = 3

3^3 = 27

3^3^3 = 7,625,597,484,987

3^3^3^3 = a 3.6 trillion-digit number, way bigger than a googol, that would wrap around the Earth a couple hundred times if you wrote it out

3^3^3^3^3 = a number with a 3.6 trillion-digit exponent, way way bigger than a googolplex and a number you couldn’t come close to writing in the observable universe, let alone multiplying out

Pretty insane growth, right?

And that’s only the top few centimeters of the sun tower.

sun tower

Once we get a meter down, the number is truly far, far, far bigger than we could ever fathom. And that’s a meter down.

The tower goes down 150 million kilometers.

Let’s call the final outcome of this multiplied-out sun tower INSANITY in all caps. We can’t comprehend even a few centimeters multiplied out, so 150 million km is gonna be called INSANITY and we’ll just live with it.

So back to where we were:

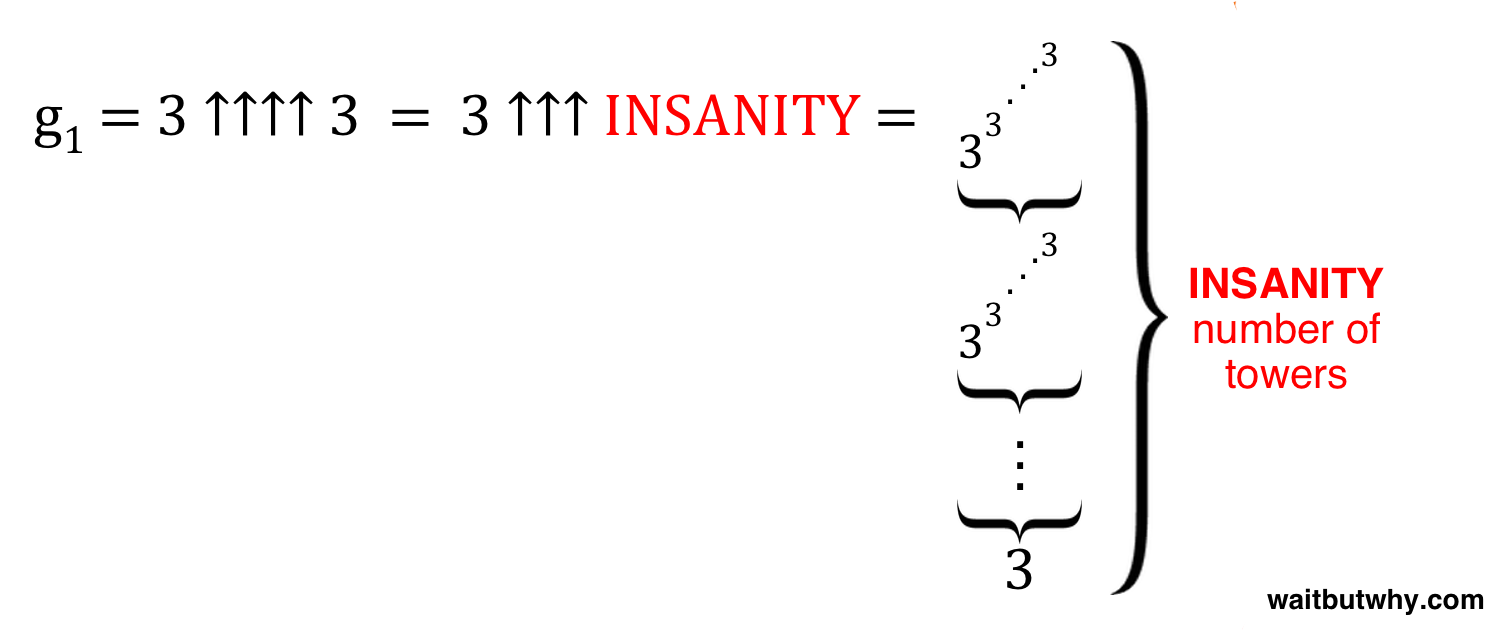

g1 = 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3 = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ 3) = 3 ↑↑↑ (sun tower)

And now we can replace the sun tower with the final number that it produces:

g1 = 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3 = 3 ↑↑↑ (3 ↑↑↑ 3) = 3 ↑↑↑ (sun tower) = 3 ↑↑↑ INSANITY

Alright, we’re ready for the second of our two feeding frenzies. And here’s the thing about this second feeding frenzy—

So you know how upset I just got about this whole INSANITY thing?

That was the outcome of a feeding frenzy with only two towers. The first little one multiplied out and fed into the second one and the outcome was INSANITY.

Now for this second feeding frenzy…

There are an INSANITY number of towers.

We’ll move on in a minute, and I’ll stop doing these dramatic one sentence paragraphs, I promise—but just absorb that for a second. INSANITY was so big there was no way to talk about it. Planck volumes in the universe is a joke. A googolplex is laughable. It’s too big to be part of my life. And that’s the number of towers in the second feeding frenzy.

insanity

So we have an INSANITY number of towers, each one being multiplied allllllllll the way down to determine the height of the next one, until somehow, somewhere, at some point in a future universe, we multiply our final tower of this second feeding frenzy out…and that number—let’s call it NO I CAN’T EVEN—is the final outcome of the 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3 power tower feeding frenzy psycho festival.

That number—NO I CAN’T EVEN—is g1.

Now…

I want you to look at me, and I want you to listen to me.

We’re about to enter a whole new realm of craziness, and I’m gonna say some shit that’s not okay. Are you ready?

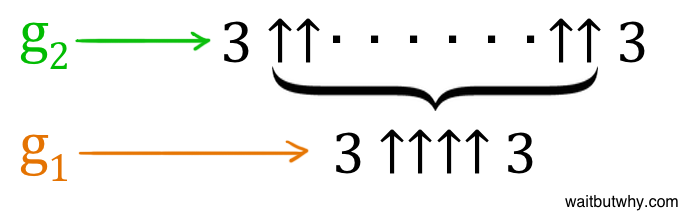

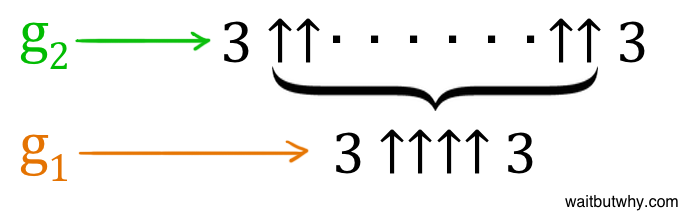

So g1 is 3 ↑↑↑↑ 3, aka NO I CAN’T EVEN.

The next step is we need to get to g2. Here’s how we get there:

g2

Look closely at that drawing until you realize how not okay it is. Then let’s continue.

So yeah. We spent all day clawing our way up from one arrow to four, coping with the hardships each new operation level presented us with, absorbing the outrageous effect of adding each new arrow in. We went slowly and steadily and we ended up at NO I CAN’T EVEN.

Then Graham decides that for g2, he’ll just do the same thing as he did in g1, except instead of four arrows, there would be NO I CAN’T EVEN arrows.

Arrows. The entire g1 now feeds into g2 as its number of arrows.

Just going to a fifth arrow would have made my head explode, but the number of arrows in g2 isn’t five—it’s far, far more than the number of Planck volumes that could fit in the universe, far, far more than a googolplex, and far, far more than INSANITY. And that’s the number of arrows. That’s the level of operation g2 uses. Graham’s number iterates on the concept of iterations. It bundles the hyperoperation sequence itself.

Of course, we won’t even pretend to do anything with that information other than laugh at it, stare at it, and be aroused by it. There’s nothing we could possibly say about g2, so we won’t.

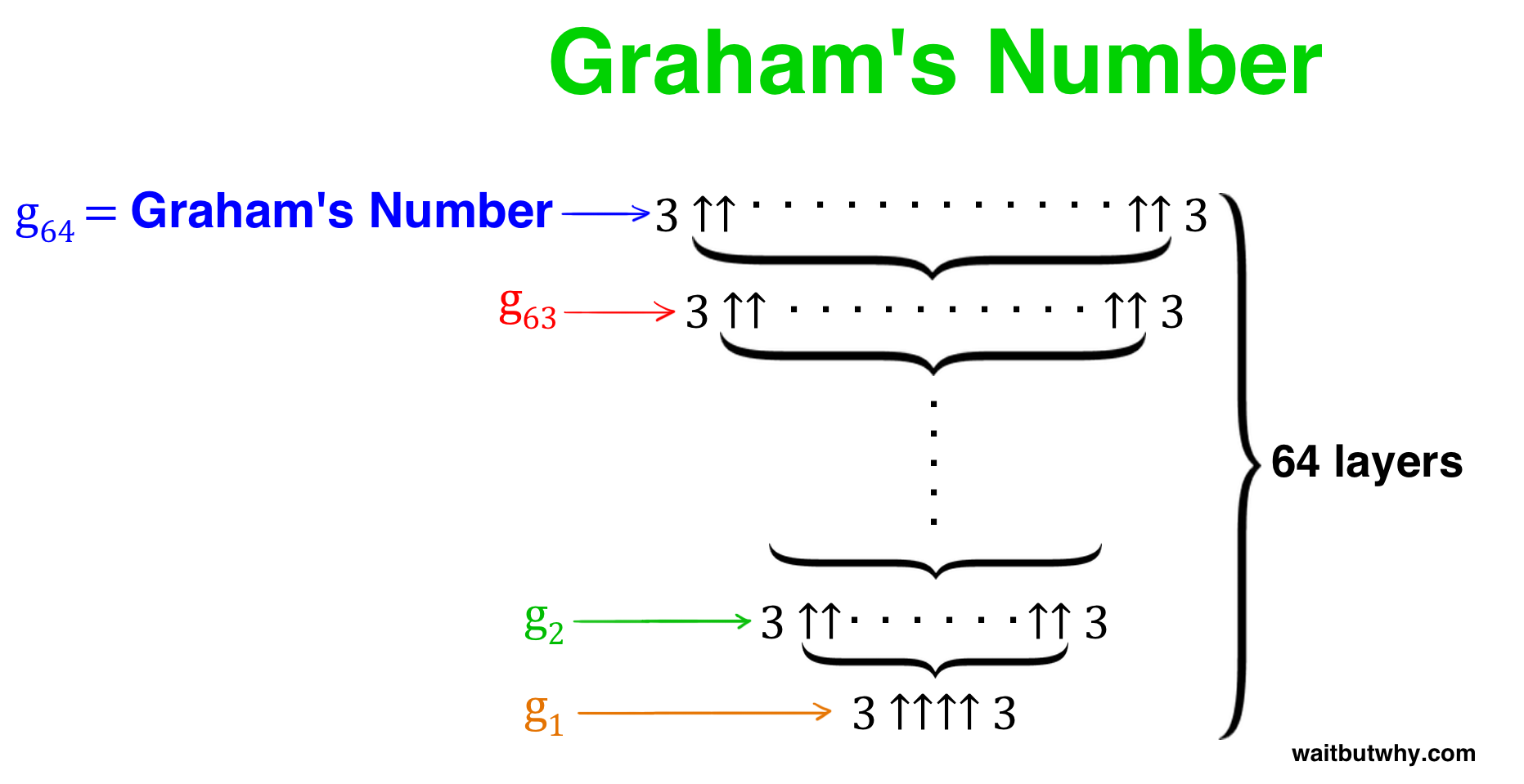

And how about g3?

You guessed it—once the laughable g2 is all multiplied out, that becomes the number of arrows in g3.

And then this happens again for g4. And again for g5. And again and again and again, all the way up to g64.

g64 is Graham’s number.

All together, it looks like this:

grahams number

So there you go. A new thing to have nightmares about.

Kc schrieb am 26.10.2013:Ich frag mich ehrlich gesagt, wozu sowas nützlich sein soll.

perttivalkonen schrieb:Dieses Bild besteht aus 213200 Pixeln zu je 24 Bit je Pixel. Daraus ergeben sich immens viele Möglichkeiten, was auf so einem Bild mit 533x400 Pixeln dargestellt werden könnten. Und zwar sind das 24^213200 Möglichkeiten.

perttivalkonen schrieb:Für das Foto da oben gibt es übrigens knapp 10^300.000 verschiedene Motive.

Suppenhahn schrieb:1,913x10^1.540.310

Original anzeigen (0,1 MB)

Original anzeigen (0,1 MB) Original anzeigen (0,2 MB)

Original anzeigen (0,2 MB) Original anzeigen (0,2 MB)

Original anzeigen (0,2 MB)

perttivalkonen schrieb:Ein Googolplexplex liegt genauso wahnsinnsmäßig über dem Googolplex. Und nun nimm also ein Googol mit 1,73 mal 10^17 Plexen dahinter. Würden wir ein Mikrogramm Tinte für ein "plex" benötigen, bräuchten wir 173.000 Tonnen Tinte zum Ausschreiben.