Narrenschiffer

Diskussionsleiter

Profil anzeigen

Private Nachricht

Link kopieren

Lesezeichen setzen

dabei seit 2013Unterstützer

Profil anzeigen

Private Nachricht

Link kopieren

Lesezeichen setzen

Martin Sand - Technological Utopianism and the Idea of Justice

08.05.2025 um 00:10

Martin Sand studierte Europäische Kultur und Ideengeschichte in Karlsruhe und promovierte dort am Institut für Technikfolgenabschätzung und Systemanalyse. Beruflich war er an der Universität Kaiserslautern im Bereich Wirtschaftsethik tätig und ist derzeit Assistenzprofessor am Department of Values, Technology and Innovation an der TU Delft. Dieser Band ist vom Springer Wissenschaftsverlag online frei verfügbar.

Dieser Band hat mich wegen des Titels interessiert, aber was ich gelesen habe, ist vermutlich der schwächste Text eines Akademikers, der mir je untergekommen ist. Dass in diesem Band außer Schlagwörtern wie Biotechnologie, Transhumanismus, Mikrochemie, Virtuale Realität irgendetwas Konkretes über technologische Utopien zu lesen ist: Fehlanzeige. Bezug genommen wird auf 1984 von Orwell und Schöne Neue Welt von Huxley, ansonsten nichts. Abgearbeitet wird sich an anderen Theoretikern, die über dieses Thema geschrieben haben, und ein spezieller Reibebaum ist für den Autor Karl Popper.

Zu Beginn ist Sand wichtig, dass Utopien wert sind, sich dafür zu engagieren, aber mehr? Es wird darauf nicht eingegangen. Zwar wird konstatiert, dass technologische Utopien für ein besseres Leben eintreten, aber den politisch-gesellschaftlichen Bereich ausklammerten. Beispiele? Nope. Völlig absurd wird es, wenn er Transhumanisten vorwirft, dass sie weiß, männlich, nicht behindert seien und nicht aus aus der bildungsfernen Schicht stammten.

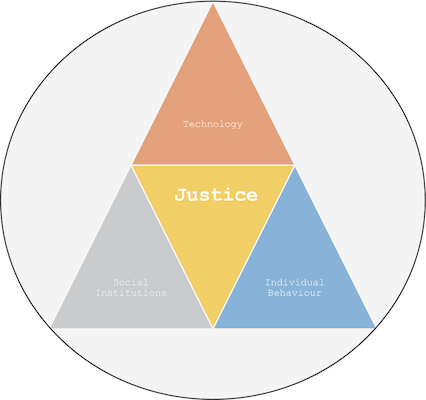

When looking at the forerunners of the Transhumanist movement, we find CEOs of big tech companies (Ray Kurzweil), university professors (Nick Bostrom) and other white, male, able-bodied individuals that come from affluent backgrounds and enjoyed a high educationZum Thema Gerechtigkeit ist Sand der Ansicht, dass wahre Gerechtigkeit ein Zusammenspiel von sozialen Institutionen (wohl auch Gesetzen), individuellem Verhalten und Technologie bedürfe. Schematisiert wird es mit Bauklötzen:

Wenn er daraufhin postuliert, dass eine Gesellschaft einer gerechten Geschlechterbeziehung auch bei Gleichstellungsgesetzen nicht existiere, solange Frauen in privaten Beziehungen oder Familien nicht als gleichberechtigt gesehen werden, so werfe ich dem Text vor, dass er die wegweisenden Gesetzgebungen der 1970er Jahre in Deutschland oder Österreich als Grundvoraussetzung einer gesellschaftlichen Entwicklung schlichtweg ignoriert.

Komplett skurril wird es, wenn er Nick Bostroms These, dass Gentechnologie nicht für Reiche entwickelt werden solle, die damit sich ein längeres und gesünderes Leben erkaufen, sondern für die Heilung von an Genkrankheiten Leidenden eingesetzt werden solle, mit der Mordideologie der Nationalsozialisten vergleicht.

Bostrom:

the trajectory of human genetic enhancement may be one in which the first thing to happen is that the lot of the genetically worst-off is radically improved, through the elimination of diseases such as Tay Sachs, Lesch-Nyhan, Downs Syndrome, and early-onset Alzheimer’s diseaseSand:

The history of eugenics embarks its horrific journey based on the notion that some lives are more worthy of living than others and we find such convictions clearly in those remarks by Bostrom.Für mich stellt sich die Frage, ob Sand schwere Leseverstehensschwierigkeiten hat oder ob er schlichtweg bösartig ist. So lehnt er den Wunsch der Transhumanisten ab, dass das reale Leben für alle verbessert wird,

What Transhumanists ask us (among a lot of other things) is, thus: Must we really accept that for many people to have a decent quality of life, with sufficient food, shelter and education to provide some basic opportunities of flourishing, that others must give up some of their goods? Does widespread flourishing require that some peoples’ liberties, their freedom to own things, must be curtailed? Could there not be plenty for everyone? A view that supports the creation of plenty and widespread distribution of various material goods for everyone, does not necessarily entail that everyone needs to receive the same: There could remain varying degrees of plentitude.sondern ihm genügt eine Welt, in der Benachteiligte in einer virtuellen Umgebung sich glücklich fühlen:

Aside from conflicting values that make impossible the simultaneous enactment of different ideals of the good life in reality, there are other constraints that could be overcome in the virtual world: Some people might have wanted to become a firefighter, but have latex allergy, or they might have wanted to become a body builder but are prone to injuries, etc.Das Schlussstatement kommt aus heiterem Himmel. Sand lehnt zwar nationalsozialistische Utopien ab, findet aber gut, dass es sie gibt.

Consider, Nazi utopias of living in the prairies of the East or in the North (Stratigakos, 2022). The Nazis joggled grandeur visions of living in the vast prairies of the East, weirdly combining in these fancies of high-tech militarization with pagan mythology—blood and ground—to connect farming and peaceful, ethnically and socially cleansed Arian village life (Fest, 1991, pp. 52 f.). These narratives have been considered as utopias, too, perhaps with good reasons. Must I consider it somehow as good that these visions are around, and are they also worthy of engagement, thus? Given my lack of commitment to a definition of utopia, I cannot deny on grounds of definition the applicability of the utopian concept to those visions, although my bowel revolts when thinking of such images of ethnically cleansed communities as a better way of living and being. Still, I will bite the bullet and agree that it is somehow good that even such abhorrent and evil visions are around.Auf diese Aussage starre ich wie das Kaninchen auf die Schlange.

Dann wundert aber auch dieser Satz nicht mehr:

Someone’s liberal democracy is someone else’s inegalitarian, white patriarchy.